Out of guilt from shooting down my co-blogger’s noble campaign to get me to go to the Salazar v. Buono hearing this morning (I am sorry, but I do not get out of bed at 5:30am for the Establishment Clause), I figured I’d make up for it by at least writing a little about the case.

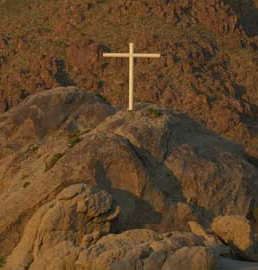

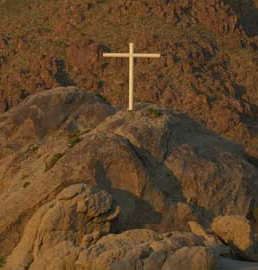

If you want to know more about Salazar, check out Scotuswiki’s write up, but, in brief: smallish cross on federal preserve, National Park Service decided to take it down, Congress forbid the use of any federal funds in taking it down, Buono sued under the Establishment Clause, court agreed with Buono, cross was put in a box, Congress sold the land the cross was on to a private group, government alleges that fixed any problem, Buono kept suing alleging that the transfer was invalid, district court ageed, Ninth Circuit agreed, now they argue about it before SCOTUS.

The mere selling off of the property doesn’t fix things by itself. The federal government maintains some control over the cross still as they designated the cross a national memorial. One of only 45 in the U.S. It’s pretty clear Congress took special measures to save the monument because it was a cross — no one could in good faith believe they’d take such attentive care of it has it been depiction of Ganesh. Moreover, government ownership or non-ownership of the monument is not itself dispositive — in last term’s Summum decision, Judge Alito noted that “persons who observe donated monuments routinely—and reasonably—interpret them as conveying some message on the property owner’s behalf . . . . This is true whether the monument is located on private property or on public property, such as national, state, or city park land.”

Besides, a general hallmark of private speech is the ability to change the content of your speech or to cease speaking all together. The owners of the Sunrise Rock Cross have no such ability. Under 18 U.S.C. §1369, they would apparently be committing a federal crime if they tried to change or destroy the monument. So it’s not really “private” speech if the government is requiring the speech, on penalty of imprisonment.

But ignoring the merits for now, I want to take a look at the procedural issues. On appeal, the government is raising two issues: first, that Buono lacks requisite standing as his harm is “ideological” rather than “religious,” and second, Congress’ transfer of the land the cross is on to a private party successfully remedied any constitutional problems that had existed.

The standing issue is actually pretty interesting, especially Buono’s arguments that the court lacks jurisdiction to hear Salazar’s argument that Buono lacked jurisdiction. Buono alleges that (1) If the government wanted to appeal the standing issue, it had to do so within 90 days of Buono I (2004), which they did not, and (2) Anyway that claim is barred by res judicata. As for the merits as to standing, basically, in these lines of cases, plaintiffs’ allege injuries that boil down to some version of “but it hurts my feelings.” Offended sensibilities normally do not provide for standing, but in the context of the Establishment Clause, a lot of the time offended sensibilities truly are going to be the biggest injury suffered — so if “offense” isn’t particularized enough of an injury, a huge chunk of EC violations will be immune to review.

The standing issue is actually pretty interesting, especially Buono’s arguments that the court lacks jurisdiction to hear Salazar’s argument that Buono lacked jurisdiction. Buono alleges that (1) If the government wanted to appeal the standing issue, it had to do so within 90 days of Buono I (2004), which they did not, and (2) Anyway that claim is barred by res judicata. As for the merits as to standing, basically, in these lines of cases, plaintiffs’ allege injuries that boil down to some version of “but it hurts my feelings.” Offended sensibilities normally do not provide for standing, but in the context of the Establishment Clause, a lot of the time offended sensibilities truly are going to be the biggest injury suffered — so if “offense” isn’t particularized enough of an injury, a huge chunk of EC violations will be immune to review.

But let’s say we get through all the procedural arguments, hear it on the merits, and Buono wins. What is his remedy now?

One issue arises from what Buono himself alleges the harm to be. Buono, a Roman Catholic, has specifically stated he has no particular objection to the displaying of religious symbols on government property, he just thought that the preserve should be open to displays of all faiths. (A Buddhist group requested and was denied permission to put up their own monument in 1999). So the most straight forward remedy to Buono’s injury wouldn’t really be simply chucking out the old monument, when in itself its not causing the harm.

So conceivably it could be remedied by simply allowing any religious group that wanted to put up a monument to do so. Now, this is Not Going To Happen. Once people from kooky sects all over the place start showing up asking permission to put up their monument of their god, which just happens to resemble sexually explicit imagery/depictions of Jesus as a cyborg/Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, they will quickly reach a decision to remove all religious imagery rather than allow any. (Mojave has 1.6 million acres — you can fit a lot of religious paraphernalia in there if you were going to allow that.)

And I don’t think the Court would find (assuming again the Court manages to wade through all the standing issues to get there, which is doubtful) that any Establishment Clause violation is fixed simply by removing all further government interest in the monument, such as its designation or the federal ability to continue to regulate it. The major issue is that the cross strongly appears to be government endorsed speech, removing a few additional government entanglements won’t solve that. So the remedy would be to remove the cross.

Now, although the land was sold off, the government still maintains a number of interests in the cross, including a property interest in the possibility of reverter, which was provided for under the bill that decreed the land transfer, § 8121. Ignoring how this concerns the merits of the case, how might this it affect any possible remedy assuming a violation is found?

In Salazar, that’s all pretty clear. The district court enjoined the actual land transfer, even though the “mechanics” of it were completed, so the Supreme Court could simply uphold the injunction. Even if the sale could not be enjoined, thanks to the cross’s status as a monument, there are a number of other ways the government could be ordered to take back control of the land and remedy the violation. From the Ninth Circuit’s opinion,

Even if the land were transferred under § 8121(a), it may revert to the government under § 8121(e), or as provided in other statutes. In particular, we noted that 16 U.S.C. § 431 authorizes relinquishment of lands containing “national monuments” to the federal government, and 16 U.S.C. § 410aaa-56 authorizes the Department of the Interior to “acquire all lands and interest in lands within the boundary of the [Mojave] preserve by donation, purchase, or exchange.”

But what about in a case where this isn’t clear cut? I don’t know enough about this area of law to predict what would happen, but it seems to me there are some seriously thorny issues that could arise here, in a similar case where the transfer is not enjoinable and there are no other statutes that can be used to get it back.

What’s to stop the government from building a couple dozen giant statutes on various federal lands that declare “Ahura Mazda is Our Lord”, and then selling off all the patches to private bidders? Assuming all the formalities of the sale are complied with, fair consideration is given by the private party, etc., what remedy would even be available? Would there now be a Takings Clause issue, if the government were ordered to take the land back and take down the Ahuras? What if the properties have changed hands a few times since the initial transfer? Or it had been twenty years? Or if the new owners “promised” to take down the monuments, but kept randomly putting them back up from time to time? I think this is my primary issue with the government’s case in Salazar: it proves too much. And trying to fix any mess created would not be a simple task.

Finally, for a brief note on the actual merits–

Cases like Salazar are fairly frequent, and the vast majority of them involve the government displaying Christian symbols and refusing to allow non-mainstream-Christian faiths to display their own. The pattern is unmistakable — the government will defend to its last legal breath its ability to display indicia of adherence to the Christian faith, but not any other symbol of religious worship. It’s the pervasive pattern, rather than any one odd cross up on a hill somewhere, that causes the Establishment Clause concerns. No, the Sunrise Rock Cross does not in itself a threat to religious liberties or the First Amendment, but the disparate impact of the government’s choice in which monuments to defend is itself a violation of the Establishment Clause.

-Susan

The standing issue is actually pretty interesting, especially Buono’s arguments that the court lacks jurisdiction to hear Salazar’s argument that Buono lacked jurisdiction. Buono alleges that (1) If the government wanted to appeal the standing issue, it had to do so within 90 days of Buono I (2004), which they did not, and (2) Anyway that claim is barred by res judicata. As for the merits as to standing, basically, in these lines of cases, plaintiffs’ allege injuries that boil down to some version of “but it hurts my feelings.” Offended sensibilities normally do not provide for standing, but in the context of the Establishment Clause, a lot of the time offended sensibilities truly are going to be the biggest injury suffered — so if “offense” isn’t particularized enough of an injury, a huge chunk of EC violations will be immune to review.

The standing issue is actually pretty interesting, especially Buono’s arguments that the court lacks jurisdiction to hear Salazar’s argument that Buono lacked jurisdiction. Buono alleges that (1) If the government wanted to appeal the standing issue, it had to do so within 90 days of Buono I (2004), which they did not, and (2) Anyway that claim is barred by res judicata. As for the merits as to standing, basically, in these lines of cases, plaintiffs’ allege injuries that boil down to some version of “but it hurts my feelings.” Offended sensibilities normally do not provide for standing, but in the context of the Establishment Clause, a lot of the time offended sensibilities truly are going to be the biggest injury suffered — so if “offense” isn’t particularized enough of an injury, a huge chunk of EC violations will be immune to review.