The Strait of Hormuz, as news articles in recent weeks have repeatedly stressed, is kind of a big deal when it comes to the global oil trade. The Strait, which is a mere 20 miles across at its narrowest point, connects the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman — and also connects the rest of the world with 40% of its daily oil tanker traffic.

Which is why Iran’s recently renewed threats to close down trade through the Strait of Hormuz are risky for all concerned. Risky for the rest of the world, because any disruption would contain a severe economic toll. And risky for Iran, because if it ever actually did attempt to shut down the Strait, it would intensely piss off literally the entire world. So, while Iran periodically makes noises about taking such a move, the odds of it actually carrying out on its threats are minimal. Nevertheless, given the costs involved, the risk, however small, is taken extremely seriously by the rest of the world.

But ignoring the reality of the situation for a moment, and pretending as if international law actually possessed the power to effect state’s actions in the Gulf, would Iran actually have the legal right to carry out any of its threats?

For once, international law has a straightforward answer: no. Any attempt by Iran to close the Strait of Hormuz would be unambiguously illegal; the shipping lanes through the Strait of Hormuz, as laid out by the International Maritime Organization, lay within the territorial sea of Oman. Although the 12-mile territorial seas of Iran and Oman overlap at the narrowest points of the Strait, the deepest waters — and thus the shipping channels — lay to the south, within Oman’s territorial waters. As such, any military action by Iran to shut down shipping through Hormuz would inevitably impinge on Oman’s sovereign rights.

But Iran’s legal rights over the Strait of Hormuz vis-à-vis the rest of the world, and ignoring Oman’s sovereignty concerns, are a slightly more complicated question, although even there Iran’s claims are tenuous. The precise extent of Iran’s legal authority, however, differs based upon whether one applies the doctrine of innocent passage or transit passage to the Strait.

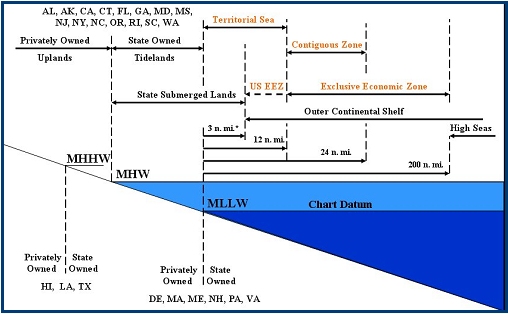

Both doctrines concern the passage of ships (as well as planes) through a nation’s territorial sea, which extends up to 12 miles from a state’s coast. The doctrine of innocent passage, which bears a greater claim to customary international law status, applies throughout all the territorial seas of the world. The concept of transit passage, in contrast, applies solely to those sections of territorial seas provide an exclusive link between two larger bodies of waters — i.e., straits.

The right of innocent passage, laid out in Articles 17 – 26 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (“UNCLOS”), protects the right of ships in transit to pass through another nation’s territorial sea, subject to certain regulations that may be imposed by the sovereign. Passage is considered innocent “so long as it is not prejudicial to the peace, good order or security of the coastal State.” Innocent passage, however, can be subject to certain conditions imposed by the sovereign state, and may in fact be suspended temporarily in times of emergency.

In contrast, transit passage, which is regulated by Articles 37 – 44 of UNCLOS, is nonsuspendable, and not limited to innocent passage. The conditions that may be imposed by sovereign states are limited, and not subject to any real teeth. So long as a ship is not engaged in any nontransit activities and complying with certain traffic and safety measures, coastal States must permit ships to pass through their territorial seas.

So if the Strait of Hormuz is governed by transit passage, Iran’s legal ability to take any action to impede transport through the strait, even against an unfriendly foreign nation’s warships, is more or less nil. If, on the other hand, the regime of innocent passage applies, Iran has a fair bit more wiggle room to work with. Particularly in a situation where hostilities are shading towards war and the use of force, where a coastal state’s territorial waters governed by a regime of innocent passage, that state has a non-negligible claim to a right to enforce extensive regulatory control over the area, up to and including an ongoing suspension of all transit rights.

The question then is whether the Strait of Hormuz is subject to transit passage or not. Textually, it would seem clear that the Strait of Hormuz falls with Article 37’s scope, as it is a “strait[] which [is] used for international navigation between one part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone and another part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone.” Thus, under UNCLOS’s text, a strait like the Strait of Hormuz — which connects the Persian Gulf’s EEZ to the Strait of Oman’s EEZ, as well as the high seas beyond — is subject to transit passage. So why doesn’t that settle the question for good as to what transit regime applies here?

Well, for one, neither the U.S. nor Iran have ever actually gotten around to ratifying UNCLOS. Since neither state has ever entered the treaty, its terms can only apply if the terms are also obligatory under customary international law. And there, opinions differ, with no few authorities holding that the general right of transit passage has yet to be established outside of treaty-conferred obligations.

On the other side of that argument is the United States, which, despite its somewhat contentious and complicated relationship with UNCLOS, has long held that the bulk of UNCLOS’s provisions are merely a codification of customary international law. This includes UNCLOS’s provisions regarding transit passage, as U.S. authorities have repeatedly asserted these norms to be a component of CIL:

…the United States…particularly rejects the assertions that the…right of transit passage through straits used for international navigation, as articulated in the [LOS] Convention, are contractual rights and not codification of existing customs or established usage. The regimes of…transit passage, as reflected in the Convention, are clearly based on customary practice of long standing and reflects the balance of rights and interests among all States, regardless of whether they have signed or ratified the Convention… (Diplomatic Note of August 17, 1987, to the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria (intermediary for Iran)).

And,

…the regime [of transit passage] applies not only in or over the waters overlapped by territorial seas but also throughout the strait and in its approaches, including areas of the territorial sea that are overlapped. The Strait of Hormuz provides a case in point: although the area of overlap of the territorial seas of Iran and Oman is relatively small, the regime of transit passage applies throughout the strait as well as in its approaches including areas of the Omani and Iranian territorial seas not overlapped by the other. (Navy JAG, telegram 061630Z June 1998).

In contrast, Iran has consistently maintained the opposite view, holding that transit passage only exists among states that have agreed to submit to that regime via ratification of an international agreement. Although Iran has not ratified UNCLOS, it has signed the convention, and with its signature it submitted the following declaration:

Notwithstanding the intended character of the Convention being one of general application and of law making nature, certain of its provisions are merely product of quid pro quo which do not necessarily purport to codify the existing customs or established usage (practice) regarded as having an obligatory character. Therefore, it seems natural and in harmony with article 34 of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, that only states parties to the Law of the Sea Convention shall be entitled to benefit from the contractual rights created therein.

In other words, Iran viewed Article 38 of UNCLOS, concerning the right of transit passage through straits used for international navigation, to be an exclusively treaty-based obligation, and not one of customary international law. As Iran never got around to ratifying UNCLOS, the implication would be that Iran does not in fact believe itself to have acceded to any such treaty obligation. This position has been confirmed by numerous assertions by Iranian officials in the decades prior to and since UNCLOS’s entry into force.

Iran is not alone in this belief about transit passage’s status under international law, either. Oman, motivated by a similar interest in the Strait of Hormuz, also filed a declaration along with both its signature to and ratification of UNCLOS, which questioned the CIL status of transit passage, and also suggested that Oman did not intend to adopt the obligations of transit passage conferred by treaty, either. Its ratification statement indicated that it only recognized and agreed to compliance with provisions concerning the regime of innocent passage — and not that of transit passage. As such, Oman’s ratification was subject to the condition that “innocent passage is guaranteed to warships through Omani territorial waters, subject to prior permission.”

Although these declarations have never actually been enforced or acted upon by either Oman or Iran, making the bulk of state practice with regards to the Strait of Hormuz to be in conformity with the existence of transit passage through the Strait, it does not appear that either coastal state believes itself to be legally bound by a customary international law of transit passage, either. Moreover, state practice and opinio juris elsewhere in the world likewise fails to unambiguously confirm the existence of a customary international law of transit passage. As such, it cannot be automatically assumed that Iran does not possess a right to limit transit through the Strait of Hormuz, at least to the extent permitted by the regime of innocent passage.

While the practical effect of transit passage’s precise status under international law will likely (definitely) be minimal in shaping events in the Persian Gulf in the days and weeks to come, parties on both sides of the dispute will be likely to invoke the application of international law in their rhetoric, as they seek to imbue their military actions with the color of law. Still, as the Strait of Hormuz does not belong to Iran alone, and Iran’s sovereign claims over the Strait are limited by Oman’s own claims to its territorial seas, any action taken by Iran to close the entirety of the Strait will necessarily be an act of force prohibited by the UN Charter, and unquestionably a violation of international law.

-Susan