There are nine states that have coastline along the South China Sea: the People’s Republic of China, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. There have been ongoing disputes for decades between those nations concerning their competing claims of sovereignty and jurisdiction over the South China Sea, as well as the islands and reef features it contains, and most of those disputes have involved China.

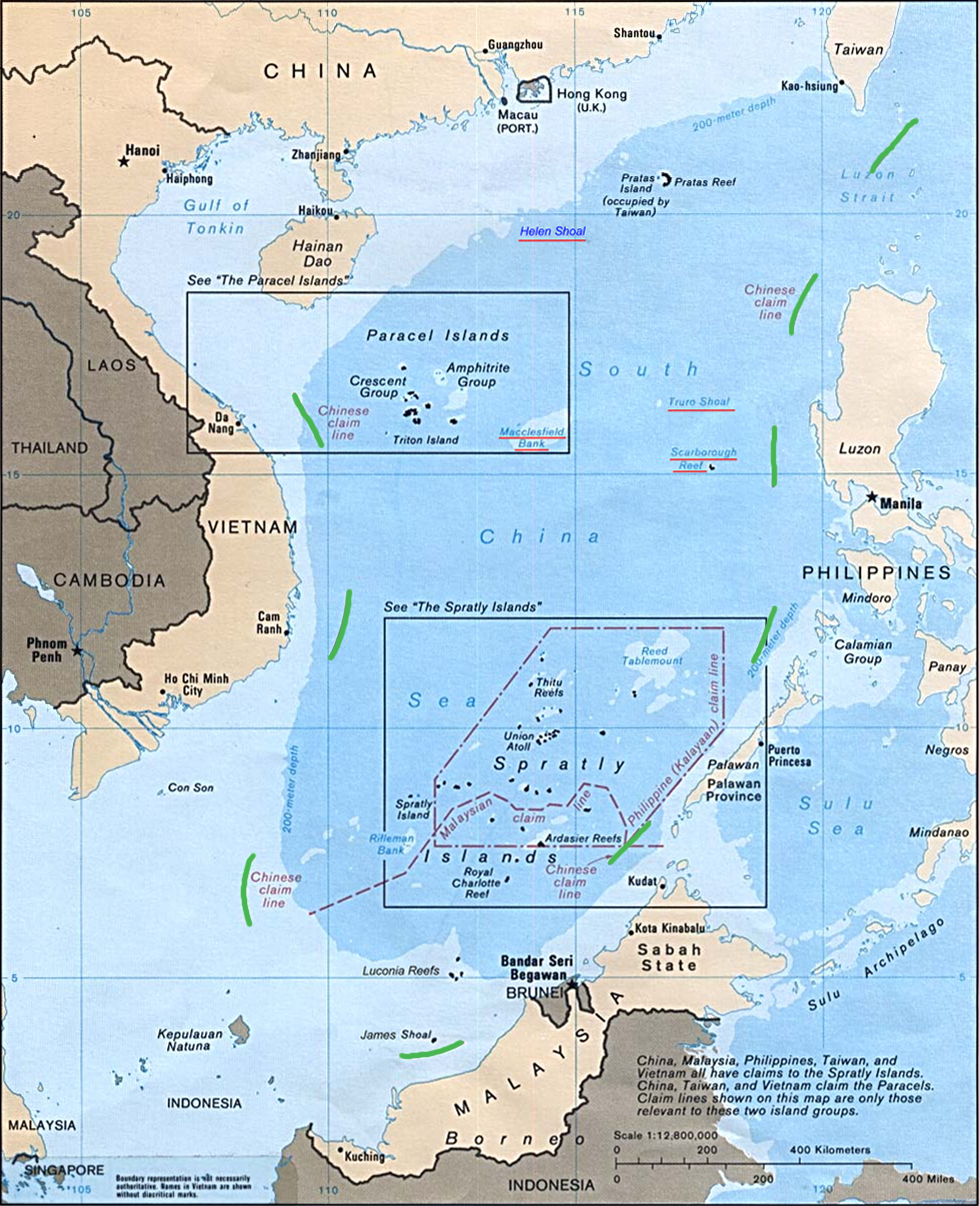

The reason for China’s leading role in these disputes can be fairly understood from a review of China’s infamous Nine-Dotted Line. This map, a version of which was submitted by China to the UN in 2009, is China’s depiction of what a fair and equitable division of jurisdiction over the South China Sea should look like:

China alleges that the extent of its claims of sovereignty over the South China Sea are based solely on its historically established territories and its lawful jurisdictional entitlements under UNCLOS and international law. The fact that these historical and legal claims provide China with self-proclaimed sovereignty over 80% of the South China Sea is, one assumes, merely a coincidence.

China’s coastal neighbors have, understandably, objected to China’s overreaching in its territorial claims under the Nine-Dotted Line, and it has been a frequent point of diplomatic contention in recent decades. Previously, however, none of the disputes concerning the South China Sea territorial claims have been successfully adjudicated by an international tribunal.

That streak may now be coming to an end. On January 22, 2013, the Philippines — perhaps finally realizing it has little to lose from taking legal action over China’s encroachments on their territories, and potentially a lot of diplomatic street cred to be gained — the Philippines filed a Statement of Claim instituting arbitration against China under Annex VII of UNCLOS,

“with respect to the dispute with China over the maritime jurisdiction of the Philippines in the West Philippine Sea, the Government of the Philippines has the honor to submit the attached Notification under Article 287 and Annex VII of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the Statement of Claim on which the Notification is based, in order to initiate arbitral proceedings to clearly establish the sovereign rights and jurisdiction of the Philippines over its maritime entitlements in the West Philippine Sea.”

China was less than impressed with the Philippines’ notice of arbitration, and promptly returned the claim to the Philippines, stating that it declined to participate in the arbitration. In refusing to participate in the mandatory and binding arbitration procedure, China is taking a gamble. Not participating in the arbitration will greatly increase the odds of the arbitration tribunal rendering an unfavorable result. China is still hoping, however, that its usual rhetoric will prevail, and that the Philippines will stand down from the legal proceedings:

“The Chinese side hopes that the Philippine side keeps its word, not to take any action that magnifies and complicates the issue, responds positively to China’s proposals on establishing a bilateral regular consultation mechanism on maritime issues, resumes the operation of the Confidence Building Measures Mechanism (CBMs) as established between the two countries, and reverts to the right track of settling the disputes through bilateral negotiations.”

The reason for China’s refusal to play ball is obvious: China’s claims are devoid of any support under any customary international law or treaty. The longer China can go without having the unlawfulness of its claims officially decreed, the better China’s chances are at having its non-lawful claims take on the color of lawful action by dint of longstanding practice. As such, China has zero interest in allowing any tribunal, binding or unbinding, to render a legal decision concerning the validity of its maritime territorial claims.

China can, and has, found a way to somewhat legally assert its indefensible claims without facing legal challenge, through bullying any states that object into agreeing to submit the dispute to diplomatic negotiations rather than legal recourses. Article 280 of UNCLOS provides that “Nothing in this Part impairs the right of any States Parties to agree at any time to settle a dispute between them concerning the interpretation or application of this Convention by any peaceful means of their own choice.” As long as China can convince (or coerce) its maritime neighbors to agree to never-ending rounds of “bilateral negotiations” and “consensus building,” then the actual lawfulness of its claims will never be tested.

But in bilateral negotiations (conveniently, China always insists on bilateral, not multilateral), the strength of each party’s bargaining position is dependent on the weight of its political resources, not the weight of its legal arguments. This is precisely what the territorial divisions and corresponding dispute resolution procedures of UNCLOS were designed to avoid. UNCLOS’s provisions reflect a core goal of the parties in entering into the Convention, which was divorcing maritime sovereignty from maritime strength. Under UNCLOS, all coastal states, no matter the size of their GDP or their military, are, theoretically, entitled to the same breadth of their territorial seas and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ). UNCLOS was designed this way, in part, to prevent larger and more developed states from going on a maritime territory claiming rampage, done solely for the purpose of establishing a historical claim to occupation and use, with the goal of fully exploiting these territories at a future date. In short, there is no “use it or lose it” clause, under UNCLOS — developing states are not at a risk of losing the natural resources in their EEZ through inaction, and so do not need to divert resources towards shoring up their claims of sovereignty. The resources are theirs, and will be their waiting once a state’s economy develops to the point where it is able to harness and use those resources for itself.

China, in contrast, has subscribed to the exact opposite philosophy when it comes to maritime claims. China’s actions are consistent with its belief that, by virtue of its size and military power, it can claim any part of the ocean that is not actually within another state’s territorial seas. China often uses the language of law in asserting its maritime claims, but China’s actions indicate that it believes its claims are, in actuality, supported by the force of its military and not by the force of law.

In filing its Statement of Claim, the Philippines is now hoping to force China into either conforming its actions with its legal claims, or else be plainly shown to be a hypocrite who is not acting within the bounds of international law. It is not as if that would come as a surprise to anyone, but in terms of drumming up global support and united opposition against China’s maritime aggression, it could go a long way in the Philippines’ favor.

But whether or not the Philippines can lawfully bring its claims before an international tribunal is not a straightforward matter. True, Part XC of UNCLOS does provide for mandatory dispute resolution procedures, either through ITLOS, Annex VII arbitrations, the ICJ, or some other adjudicative body. But under Article 298, of UNCLOS, a limited exception is provided, and “a State may, without prejudice to the obligations arising under section 1, declare in writing that it does not accept any one or more of the procedures provided for in section 2 with respect to one or more… categories of disputes.” China did in fact file a written declaration, dated August 25, 2006, which invoked the opt-out clause of Article 298, providing that “[t]he Government of the People’s Republic of China does not accept any of the procedures provided for in Section 2 of Part XV of the Convention with respect to all the categories of disputes referred to in paragraph 1 (a) (b) and (c) of Article 298 of the Convention.”

Of the three categories of disputes in Article 298, it is the category described at 298(1)(a)(i) that is likely most relevant here: “disputes concerning the interpretation or application of articles 15, 74 and 83 relating to sea boundary delimitations[.]” Although the Philippines attempted to artfully draft its Statement of Claim to avoid implicating any of the disputes within Article 298’s categories, it is likely that at least some — though not all — of the Philippines’ claims would in fact encroach on the interpretation or application of articles 15, 74, and 83.

But this doesn’t mean the Philippines cannot have all of its claims decided by an international tribunal. China’s declaration under Article 298, regarding Section 2 of Part XV, does not affect China’s obligations under Section 1 of Part XV. This means China is still bound by Article 284’s conciliation requirements:

“A State Party which is a party to a dispute concerning the interpretation or application of this Convention may invite the other party or parties to submit the dispute to conciliation in accordance with the procedure under Annex V, section 1, or another conciliation procedure …

If the invitation is not accepted or the parties do not agree upon the procedure, the conciliation proceedings shall be deemed to be terminated.”

So why didn’t the Philippines opt for mandatory conciliation? Likely because conciliation, even when mandatory, is non-binding on the parties, and the Philippines would prefer to get a judicial order in its favor. On the other hand, it is possible conciliation was already tried, and failed. In the Philippines’ Statement of Claim instituting an Annex VII ad hoc arbitration against China, the Philippines stated:

“Most recently, during a series of meetings in Manila in April 2012, the Parties once again exchanged views on these matters without arriving at a negotiated solution. As a result of the failure of negotiations, the Philippines later that month sent China a diplomatic note in which it invited China to agree to bring the dispute before an appropriate adjudicatory body. China declined the invitation.” (emphasis added)

I have not been able to locate a copy of the note, and cannot determine what the “appropriate adjudicatory body” was. It is possible that the Philippines did invite China to conciliation — but presumably, if it had, the Philippines would have specifically noted it. If the Philippines has invited China to conciliation, and China has refused the request, this would strengthen the Philippines’ claims considerably. Because UNCLOS provides for mandatory conciliation for disputes that fall within Article 298(1),

a State may, without prejudice to the obligations arising under section 1, declare … that it does not accept any … of the procedures provided for in section 2… provided that a State having made such a declaration shall, when such a dispute arises subsequent to the entry into force of this Convention and where no agreement within a reasonable period of time is reached in negotiations between the parties, at the request of any party to the dispute, accept submission of the matter to conciliation under Annex V, section 2[.]

So even if China has exempted itself from the (immediate) force of Part XV, Section 2, China is still obligated to engage in mandatory conciliation under Annex 5, Article 11:

Any party to a dispute which, in accordance with Part XV, section 3, may be submitted to conciliation under this section, may institute the proceedings by written notification addressed to the other party or parties to the dispute.

Any party to the dispute, notified under paragraph 1, shall be obliged to submit to such proceedings.

If that is what happened here — if the Philippines did give written notification to China that it wanted the parties to engage in conciliation, and China declined — then the Philippines may have some argument that it was entitled to immediately proceed with an Annex VII arbitration, and that China cannot now validly object to the arbitration tribunal’s jurisdiction. This isn’t a watertight argument — the Philippines could have proceeded with mandatory conciliation, per Art. 12 of Annex V, even if China refused to participate — but the “provided that” language of Article 298 could be read to imply that Article 298’s opt-out procedures only apply on the condition that the party accepts submission of those disputes to mandatory conciliation. If China declined to comply with the condition precedent of Article 298’s opt-out provision, then perhaps the Philippines was entitled to proceed under Section 2 of Part XV.

Additionally, the Philippines does have a viable argument that its dispute with China (or at least part of it) is not within the class of disputes that is covered by China’s Art. 298 declaration. Mandatory conciliation might not have been required in this case at all. However, given the ambiguous and unsettled question of whether an Annex VII arbitration could exercise jurisdiction over the dispute submitted by the Philippines, it should be no surprise that the Philippines selected Rüdiger Wolfrum, the former president of ITLOS, as its designated arbitrator. Judge Wolfrum has already gone on the record stating that he believes UNCLOS tribunals have the jurisdiction to hear maritime delimitation disputes that arise in the context of UNCLOS provisions that do not directly concern delimitation, but may indirectly affect it:

there can be no doubt that disputes concerning the interpretation or application of other provisions, that is, those regarding the territorial sea, internal waters, baselines and closing lines, archipelagic baselines, the breadth of maritime zones and islands, are disputes concerning the Convention (see articles 3 to 15, 47, 48, 50, 57, 76 and 121).

Although far from conclusive, it does suggest Judge Wolfrum may be willing to find that a maritime delimitation dispute of the type brought by the Philippines arises under UNCLOS pursuant to articles other than 74 and 83. If so, that would give the Philippines at least one potential vote on the arbitration panel — and a persuasive one, at that — in favor of an Annex VII tribunal finding in favor of its own jurisdiction to adjudicate the Philippines’ claims.

-Susan