Last year, Michigan high school teacher Jay McDowell kicked a student out of his classroom, for what the teacher described as disruptive behavior. Normally, the rest of the world would never have heard of this event; kids get kicked out of classrooms for being disruptive every day, and very rarely does it make headlines. McDowell, however, kicked a kid out of his classroom after the student, Daniel Glowacki, made statements to the effect that he found gay rights offensive, and that he would not accept gay individuals.

This was immediately seized upon as evidence of the homosexual agenda in action, with opponents of McDowell touting it as proof that “gay rights” are trampling religious freedoms across the land. McDowell’s defenders, on the other hand, described his decision to remove the student as appropriate, believing that the student’s behavior was disruptive and hostile to other students. The school board initially chose to suspend McDowell for one day without pay as a result of the incident, but later reversed its decision.

The matter had died away after that. Until last Friday, when the student’s mother, represented by the Thomas More Legal Center, a “public interest law firm dedicated to the defense and promotion of the religious freedom of Christians”, filed suit against McDowell and the school district over the incident, alleging that her sons’ Constitutional rights were violated. A copy of the complaint can be found here.

The purpose of the suit isn’t the plaintiff’s material gain, but rather a chance to get a court order prohibiting public schools from restricting students’ rights to make anti-gay statements while at school. Richard Thompson, president of the Thomas More Law Center, had stated that the purpose of the litigation is to defend “religious opposition to homosexuality”:

“This case points out the outrageous way in which homosexual activists have turned our public schools into indoctrination centers,” said Thompson. He said by utilizing the tyranny of political correctness, homosexual activists “are seeking to eradicate all religious and moral opposition to their agenda.”

Despite the media coverage surrounding the case, however, the plaintiff in Glowacki v. Howell Public School District is not actually asserting any claims based directly upon freedom of religion. Rather than invoking the Free Exercise Clause, the plaintiff is instead alleging (1) that the defendants deprived students of their First Amendment rights to free speech by punishing Glowacki for expressing his refusal to accept homosexuality, and (2) that the Defendants violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment “[b]y favoring speech that approves of and promotes homosexuality over Plaintiffs’ religious speech.” (The EPC claim is based on an infringement of Glowacki’s fundamental Free Speech rights rather than his group membership, as “people who have a religious viewpoint critical of homosexuality” is not a class that can invoke the court’s heightened scrutiny.)

The reason Glowacki’s case is a free speech case and not a free exercise case is obvious: his claims are far more compelling when brought under the rubric of free speech than they are when presented as religious freedom claims. In places, the Complaint does in fact invoke the specter of religious freedom as support of his claim for relief, but they are the weakest portions of Glowacki’s pleading. In short, Glowacki’s case, to the extent that it is based on religious freedoms, is that, as a Catholic, he has “a duty and obligation to defend [his] faith in public, including a duty to speak the truth about homosexuality” (Complaint, at para. 46) — that ‘truth’ being that “homosexual acts [are] acts of grave depravity, [and] that homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered” (Complaint, at para. 45).

But this is not a “duty and obligation” that the Constitution recognizes. There is no special Constitutional protection for a religious belief that “compels” you to affirm your disapproval of your fellow classmates every time the subject of their identity is mentioned. For instance, someone who claimed his religious beliefs compelled him to believe that Jews deserved to be exterminated would not thereby acquire a right to announce such a belief every time the subject of the Holocaust came up in class.

And so Glowacki focuses on free speech, not free exercise. But although Glowacki’s free speech claims are legitimate under the facts he has alleged, his Complaint is still pretty appalling in many respects. For instance, it describes the school district’s anti-bullying campaign as “a day in which activists exploit the tragic suicidal deaths of homosexual teenagers to promote acceptance of homosexuality in the public schools.” (Complaint, at 26). It also refers to the “pro-gay agenda” seven times, and comes off sounding rather paranoid in the process. Worse still, it repeatedly describes the suicides of kids who were bullied due to their perceived sexual orientation as “teenagers who committed suicide because they were homosexual. ” (Id., at 39). The Complaint continues to win itself no favors when it alleges that “the purpose of the ‘anti-bullying day'” is “to shift the blame for the destructive lifestyle of homosexuals to those who believe it is wrong and immoral”. In other words: gay students deserve to be harassed, and any harassment they receive due to their sexual orientation is their own fault for being gay.

But as unpalatable as the Complaint is, assuming everything it says as true, Glowacki likely does have a case. That is a pretty big assumption to start from, however; although both Glowacki and McDowell do seem to agree on some of the central facts in the dispute, the parties are diametrically opposed as to what the general tone of the exchange was, or what the intentions of the parties were. And here, the tone of the exchange is everything.

Rather than breaking new legal territory, I expect this will ultimately be a heavily fact-based case. Comparing the claims of the two sides, however, gives an indication as to where this suit is headed:

Plaintiff Glowacki’s Story:

47. On October 20, 2010, during his sixth hour economic class in which Plaintiff D.K.G. was a student, Defendant McDowell explained to the students that it was the national “anti-bullying” day and that the students were going to watch a movie about teenagers who committed suicide because they were homosexual.

48. At the beginning of the instruction and in front of the entire class, Defendant McDowell confronted a female student who was wearing a Confederate flag belt buckle. Defendant McDowell directed the student to remove the article of clothing because he considered it offensive. The female student had worn this belt and buckle to class on several prior occasions without receiving a reprimand.

49. In light of Defendant McDowell’s opening remarks to the student about “antibullying” day and tolerance, Plaintiff D.K.G. raised his hand and asked Defendant McDowell why it was permissible to display a rainbow flag, which is offensive to some people, but not a Confederate flag, which Defendant McDowell found offensive.

50. Offended by the question, Defendant McDowell curtly responded by stating that the rainbow flag represents the gay community, but the Confederate flag “represents killing people and hanging and skinning people alive,” or words to that effect.

51. Defendant McDowell then asked Plaintiff D.K.G. whether he “supported” or “accepted gays,” or words to that effect. Plaintiff D.K.G. responded by stating that his religion does not accept homosexuality and that he could not condone that behavior. Angered by the response, Defendant McDowell told Plaintiff D.K.G. that his religion was “wrong,” or words to that effect, and ordered Plaintiff D.K.G. to leave his classroom under threat of suspension.

52. After ordering Plaintiff D.K.G. to leave the classroom, Defendant McDowell asked the remainder of the class whether anyone else did not accept homosexuality. A student raised his hand, and Defendant McDowell ordered him out of the classroom as well.

Defendant McDowell’s Story:

At the beginning of my 6th hour students asked what the “Tyler’s Army” t-shirts were about. This led to the beginning of a discussion about anti-bullying. It was a discussion about not bullying anyone due to race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or social status. One female student entered the class wearing a Confederate Flag belt buckle. This student knows that I have not allowed Confederate Flags in my class. She sits in the front row. I asked her to remove the belt buckle and she did so without incident. At this point, a male student raised his hand and asked why she had to remove the belt buckle. I explained that the Confederate Flag is often seen as a symbol of discrimination. The student then said “well Gays get to fly their rainbow flag.” This was a disruption to the classroom environment. I explained the rainbow flag is not a part of the discussion and that it hasn’t been associated with lynchings, mob violence, or discrimination in the way that the Confederate Flag has been. The student then said, “I don’t accept Gays.” Obviously this was an inappropriate thing to blurt out in class and had no place in the discussion. I told him he could not say that in class that it was inappropriate. He asked, “Why? I don’t accept Gays. It is against my religion. I am Catholic.” I said that was fine it was against his religion but that that statement was inappropriate to say in class. I became concerned at this time as there were students in the class that his comment would affect in an adverse way. There were at least ten students in the class wearing purple on that day. I related the situation to discrimination against African-Americans. I explained to the class that just as you can’t say, “I don’t accept blacks” in class you can’t say “I don’t accept Gays” in class. You can have whatever religious beliefs you want but there are statements that are inappropriate to say in class. I suspended him from class that day and wrote up a referral for unacceptable behavior. Another male student walked in at that moment and said loudly, “well I don’t accept Gays either can I leave.” I said, “yes get out.” Both students were insubordinate in class and caused a disruption of the class.

The accounts do overlap, but the differences between them are determinative. Under Glowacki’s version of the facts, he wins. Under McDowell’s version, he was in the right. So whose story is true?

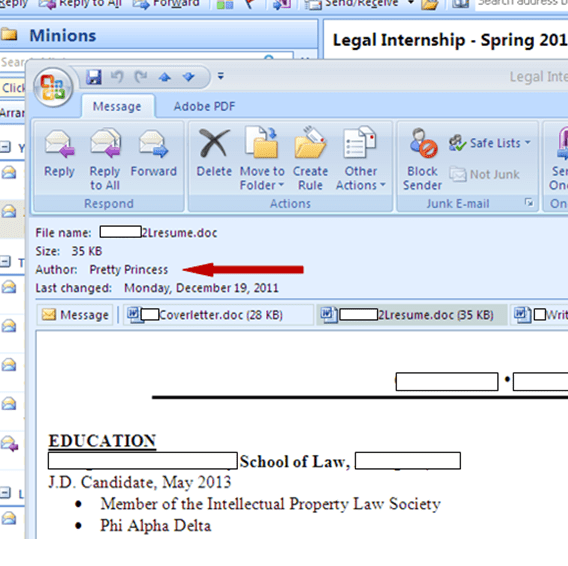

It is not clear one way or another, at this stage of the proceedings. However — and while I am aware that my biases are now shining through bright and clear here — I have severe doubts about Glowacki’s ability to prove his version of events. Glowacki’s story just doesn’t pass the smell test: a kid that that speaks up to defend a classmate’s prerogative to display the Confederate flag in class is not a kid that then will follow up by opposing gay rights by demurely stating that “he could not condone that behavior.” In fact, the Complaint completely dodges away from identifying the actual language used by Glowacki in the exchange, leaving the student’s own words vague and unspecified. But note that the Complaint portray McDowell’s words as if they were direct quotes — only to then hide behind the disclaimer that McDowell’s statement might actually have just been “words to that effect,” rather than the actual words used. Meanwhile, the Complaint only paraphrases Glowacki’s own statements, thereby framing him in as inoffensive a manner as possible.

Although I do think it seems likely that McDowell overreacted in dismissing Glowacki from the classroom, my bet is that Glowacki was in fact being disruptive at the time, and was not merely expressing his religious views in a respectful fashion. It was Glowacki, remember, that initiated the exchange when he, unprompted, decided to equate a gay rights symbol with the Confederate flag. As a native Georgian, I am well aware that individual perceptions of the stars and bars can and do vary, but even the most charitable part of me is very skeptical that there is an innocent justification for a kid from Michigan to be defending the right to display the Confederate flag. Moreover, Confederate flags were not a neutral symbol to this student body — a year prior, a group of students at Howell had used school computers to create a racist facebook group that used a confederate flag as its icon:

The group’s Web page displayed an image of the Confederate flag along with this message:

“If you hate a certain type of anybody black, white, pink, yellow or polka dot (you) should join. This shows you are a rebel and proud of it.”

Given this background, I’d say Glowacki’s got an uphill battle in proving that his statements were as innocent and non-disruptive as he claims.

And the precise words Glowacki used — and the tone in which he said them — matters here, a lot. For instance, several unsubstantiated reports about the incident have stated that other students in the class reported Glowacki saying “those faggots” during the course of the exchange. The reports state that these statements were made only to classmates, however. But if, for example, McDowell had actually heard a student make statements to that effect, then the case would be open and shut. McDowell would have been on firm ground in removing Glowacki from the classroom, as schools are permitted to suppress vulgar and obscene speech, which “those faggots” would very arguably fall under. See Bethel School District v. Fraser (1986).

But assuming vulgar language was not used, the most obviously applicable precedent to this case is the Supreme Court’s decision in Morse v. Frederick (2007), a.k.a. the “bong hits 4 jesus” case. In Morse, the school was found to have a compelling interest in suppressing student speech that promoted illegal drug use. In Glowacki, the school could argue instead that its compelling interest was in suppressing speech that promotes bullying — a particular pertinent interest, given the recent attention bullying and teen suicide have received in the media in the past few years.

And discouraging bullying based on sexual orientation has already been found to be not just a compelling interest for school officials, but rather an affirmative obligation. In Flores v. Morgan Hill (2003), the 9th Circuit found that school officials were liable for failing to make any attempt to prevent persistent bullying of students that were perceived by their peers to be gay — and moreover, those school officials were not entitled to qualified immunity. Glowacki’s legal arguments, if correct, would therefore put public schools between a rock and a hard place; they would be required to protect students not only from the anti-gay animus of their classmates, but would also be required to protect students’ rights to express anti-gay animus in class.

Due to the similarities in the school official’s interests in both cases, Morse would seem to be highly determinative when it comes to Glowacki’s case. Re-wording Alito’s concurrence in Morse to change the compelling interest from discouraging drug use to discouraging bullying, you get a straight-forward defense of McDowell’s actions:

[D]ue to the special features of the school environment, school officials must have greater authority to intervene before speech [that declares gays to be “unacceptable”] leads to violence [and bullying]. And, in most cases, Tinker‘s “substantial disruption” standard permits school officials to step in before actual violence erupts.

Speech advocating [the ostracizing and disapproval of gay students] poses a threat to student safety that is just as serious, if not always as immediately obvious…. I therefore conclude that the public schools may ban speech advocating [anti-gay animus, in a disruptive fashion]. But I regard such regulation as standing at the far reaches of what the First Amendment permits

This is not to say that any speech that is pro-drug or anti-gay can be suppressed under the Morse framework; a paper advocating legalization of marijuana or arguing that Catholicism does not condone non-procreative sex could not be prohibited due to safety concerns.

This is why Glowacki v. McDowell will ultimately be decided on the facts, not the law. If Glowacki was being belligerent and hostile when he declared that gay rights were offensive to him, McDowell was justified in eventually removing him from the classroom under Morse when he continued to state that “I do not accept gays.” If instead Glowacki’s expression of religious belief was made in a non-disruptive manner, and particularly if his statement was made in response to a direct question from the teacher soliciting his views, then Glowacki should prevail.

So facts are everything, here. But luckily, as this all took place in a classroom, there should at least be quite a few eye-witnesses available to testify. I hope the Thomas More Law Center is looking forward to deposing a couple dozen teenagers — I bet that will be just loads of fun.

-Susan