[Edit, 1/17/2015: In the two months since this post was written, substantially more evidence concerning the events of January 13, 1999, has been released. As a result, I have completely revised my opinion on numerous matters discussed herein.

This post has therefore been updated to add new and more accurate maps. However, I have not yet updated much of the accompanying text, and much of my current interpretation of the cellphone data is substantially different from what it was when this post was first written.]

Like everyone else in the world, I’ve been listening to Serial. For those who haven’t listened in yet, Serial is a weekly podcast covering the murder of 18-year-old Hae Min Lee, who was killed on January 13, 1999. Her ex-boyfriend, Adnan Syed, was subsequently convicted of first-degree murder and kidnapping, and is currently serving a life sentence. (And if you haven’t listened to the podcast yet, turn back now and come back when you have. Otherwise, the minutiae of these cell phone records won’t be interesting in the slightest.)

The evidence against Adnan was complicated and deeply ambiguous. That’s unsurprising — after all, there’s a reason his case was chosen to be the subject Serial’s first season. But while there’s much we do not know about the the investigation into Hae’s murder and the state’s case against Adnan, based on what the show has covered so far, and what has been made publicly available about Adnan’s two trials, there are many reasons to be unsettled by his conviction. Even for those who think Adnan probably did plot and carry out the murder of his ex-girlfriend — and there are plenty who do — it is hard to say that there wasn’t room for some very reasonable doubts about his guilt.

Legally, there was sufficient evidence to support Adnan’s conviction; he’s not going to win any appeals there. An eye witness — Jay, Adnan’s weed dealer and casual friend — testified to his guilt. But while the jury always has the right to determine whether a witness is telling the truth, it does not appear that, in this case, there was any objective basis for crediting Jay’s testimony against Adnan (as discussed in further detail at Serial: Why Jay’s Testimony Is Not Credible Evidence of Adnan’s Guilt).

Other than Jay’s testimony, the only evidence that Adnan had any connection with Hae’s murder came from his cell phone records. As a result, understanding what those cell records show, and do not show, is a highly significant part of the case. Provided below is a summary of the data from each of the 31 calls made to or from Adnan’s cell phone that day — including the time, who the call was to, the duration, and the cell phone tower that the call was routed through — and a summary of how that data compares to the testimony and statements given by key witnesses in the case.

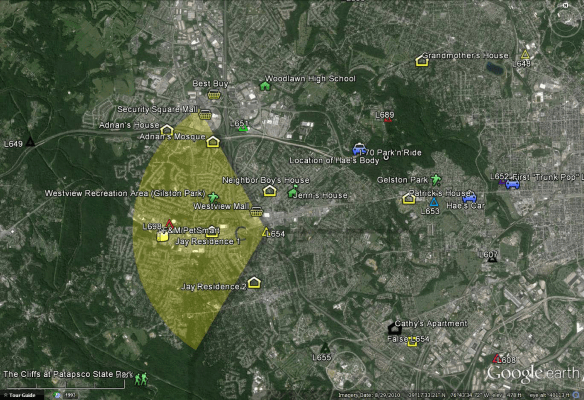

A note on the significance of the location data: It should be stressed that the tower data — that is, the record of the tower and antenna that a call was routed through — provides us with a probabilistic (and not determinative) location for where each call was made or received from. Moreover, the maps below use an oversimplified division of likely cell tower territories based purely on distances between towers, and does not take other factors into account. The fact that any particular call may have been routed through any particular tower and antenna does not mean that the call was actually made or received from within the territory immediately adjacent to that tower/antenna; calls can be routed through towers other than the one they are closest to for any number of reasons, and two calls made from the exact same location, within minutes of one another, could end up being routed through different towers. As a result, it should be assumed that some of the 31 calls made from Adnan’s phone that day were made or received from a tower other than the one the phone was closest to at the time of the call.

Taken in the aggregate, however, the tower data is very useful for assessing the likely path followed by whoever had the cell phone that day. Additionally, by comparing the tower data against both the witnesses’ known events of the day, and with the movement of the cell phone as shown from the calls that occurred before and after, we can make a good prediction as to the accuracy of the tower data for each call individually.

As there was no testimony at trial concerning the actual ranges of these towers, the below maps assume a conservative tower range of approximately two miles.

Call 1.

Time: 10:45 a.m., January 13, 1999

To: Jay

Duration: 0:28

Call pings L651A.

Adnan Calls Jay to Ask if Jay Has Gotten a Present for Stephanie

Prosecution’s Story:

On the morning of January 13th, Adnan calls Jay from school, and then during his free period drives over to Jay’s house to pick him up. Adnan plans to kill Hae that afternoon, so he leave his car and cell phone with Jay, so that Jay can pick him up after the murder has been committed.

Adnan’s Story:

According to Adnan, he called Jay from school to make sure Jay remembered to get a birthday present for his girlfriend, Stephanie. Adnan and Stephanie are also close friends, and he did not want her to be upset if Jay forgot to get her something:

I kind of had a feeling that maybe he didn’t get her a gift. And I had free periods during school. So it was not abnormal for me to leave school to go do something and then come back. So I went to his house. And I asked him, did you happen to get a present for Stephanie? He said no. So I said, if you want to, you can drop me back off to school. You can borrow my car. And you can go to the mall and get her a gift or whatever. Then just come pick me up after track practice that day. (Episode 1.)

Jay’s Stories:

Jay says that, on the morning of January 13th, Adnan called him from school and then drove over to pick him up, and they go shopping together. In some of Jay’s statements, he claims that this was the first time he learned of the murder plan. In other statements, he claims he had learned of the plan the previous day. Although he sometimes also claims that parts of the murder were planned over the phone, Jay’s stories generally claim Adnan enlisted his help in carrying out Hae’s murder while the two of them were on a shopping trip together. However, he is inconsistent as to which shopping trip this was.

The Shopping Trip on January 12th: One of Jay’s stories involves Adnan and Jay discussing Hae’s murder during a shopping trip that occurred on January 12, 1999 — the day before Hae’s murder. Jay informs Jenn of Adnan’s plan to murder Hae, but she does not react to this news:

[I] went shopping with a friend of mine, an ex-friend of mine and ah, we ah, went to ah, ah, I just believe we went to Wal-Mart. . . . We had had a conversation. . . During the conversation he stated, um, that he was going to kill that bitch, referring to Hae Lee. . . . Ah, I didn’t, I took it with contexts and stand out my inaudible. We went, he dropped, he returned me to my house ah, I paged [Jenn] um no I’m sorry. Yes I paged [Jenn], um, we went to the [ ] park. . . There I told her the conversation me and Adnan had had earlier that day. And her reaction was just about the same and then . . . Returned home about 10 o’clock, received

another call from Adnan. This time he had told me ah, that we’re gonna hook up tomorrow. And that was it for the 12th. (Jay’s Second Interview on March 15, 1999) (herein “Int.2”).

The Shopping Trip on January 13th: Jay’s other story involves a shopping trip that instead takes place on January 13th, before Hae’s murder. Adnan calls Jay from school (the 10:45 a.m. call), and then goes to pick Jay up at his house:

I believe [Adnan] called me first. Um, he probably showed up at about 11, a little after 11 , 11:30, 11, 11:30 (Int.2 at 5).

That morning [on January 13th] [Adnan] called me and we took …. we were going to the Mall. He asked me if I could do him a favor. . . [Adnan called my house] a little after ten, about ten forty-five, quarter to eleven. I woke …. that is when I woke up. I showered so it was about an hour before I left. Ah we left the house, on the way to the Mall he asked me if I could do him a favor. . . (Int.1 at 2.)

Jay also confirms, in response to a detective’s question, that Adnan “came to [Jay’s] house about quarter of twelve, [ ] about an hour [ ] after he called” (id.).

In his statements concerning the shopping trip on January 13, Jay’s stories about what mall he and Adnan went to are not consistent. He names two different locations:

[W]e headed toward Westview mall. Um, we did a little shopping together. (Jay’s First Interview on February 28, 1999) (herein “Int.1”).

We went to Security Square Mall. (Int.2.)

Continue reading →